On the Wright

Path

by Tony Seton

There are some 600,000 pilots in the United States and most every one of them has got to have entertained, at least briefly, the notion of flying into First Flight Airport this year, the hundredth anniversary of the first powered, sustained, controlled flight in a heavier-than-air machine. FFA lies next to the Wright Brothers Memorial in Kill Devil Hills, North Carolina.

Many pilots are no doubt even thinking of perhaps flying in on December 17th, the on-the-date centenary, but they should think again. Not only are the winter winds considerable -- in the range of 30 knots -- but the temperature often hovers around freezing, as it did the day of the first flight. Not ideal conditions for a celebratory arrival. Plus there will be the crowds.

To give you an idea how strong those winds are down there, from the time the Wright brothers were flying until Congress built a monument to them a quarter-century later, Big Kill Devil Hill was blown 450 feet to the southwest. Before the monument could even be erected, the sand dune had to be secured with grass and other plantings.

The Wrights erected two small buildings when they arrived; one was a hangar of sorts, and the other was their living space. Their comforts were minimal. When parts broke, they had to be shipped back by boat and train to Dayton for repair. When they needed to send a telegram, it meant a four-mile walk. They had to transport most of what they needed, along with the various aircraft they had designed and built. The aircraft were disassembled for transport and reassembled at their site.

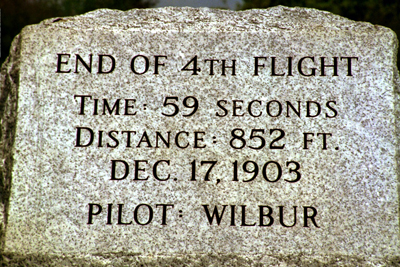

There were four flights that historic day a century ago, ranging from the first, a twelve-second jaunt spanning 120 feet by Orville, to the fourth, an 852-foot journey by brother Wilbur that lasted 59 seconds. Stone markers show where the flights started and ended, and there is a path along which visitors can walk. Itís a short walk, but it must have been a wonderfully long flight.

No wonder we returned virtually every summer for forty years. In that time, I visited the Wright Brothers Memorial a few times, enjoying the full-size replica of the original Kitty Hawk Flyer, and taking in the story-boards and photographs.

Learning about the Wrights imbued me with a need to fly into First Flight Airport. Knowing that if the weather wasnít miserable in December then the crowds would be, I decided I would like to fly into First Flight Airport in early autumn, after most of the tourists had left and the hurricane season had passed. I thought maybe Iíd tie it in with a trip back to New England to enjoy the fall colors.

First Flight Airport is not a lot more than a 3,000-by-60-foot strip of asphalt that runs parallel to the Wright brothersí course and a couple of hundred yards to the west. The southern end of runway two/two-zero starts in line with the monument on top of The Hill; the northern end stretches almost as far the stone marking the longest flight that historic day.

The airstrip was cut out of a thick tangle of trees, and though thereís plenty of room on either side, some pilots experience a churning wind-tunnel effect, especially when landing to the southwest. I know from experience.

And I mean brand new. The planes I normally rent were built in the 70's and show 7,000-plus hours on the tach; the Horizon plane I flew had 69.8 hours. It was squeaky clean with leather seats and a sparkling panel. It featured a moving map, GPS, electric trim, an HSI and an autopilot. No carb heat, of course, but a fuel pump, and myriad places under the cowling and wings from which to drain fuel. Aside from a little new plane stiffness -- not difficult to manage -- it felt like an old wife in a new body.

I had planned to be in the area for three days, and had been held up for two days by weather which had spawned fatal tornadoes in the Midwest. I was scheduled to fly back to California the third day, and wasnít sure but that I might have to schedule another trip east. But the day dawned only partly cloudy, and my plans became reality.

At Horizon, I found myself with the choice of getting checked out over CPK by flight instructor Robert Ziegenfuss, or I could fly my check ride to FFA. I had no need to fly down there alone, and who doesnít appreciate the company of someone familiar with both the aircraft and the area sitting in the right seat. Not that I needed any help, but Robertís presence lowered the attention I needed to pay to the actual flying and made it a pure pleasure flight.

I set out on a heading of 150, climbing to only 2500, to stay comfortably a thousand feet below the many small-ish cumulus clouds that dotted the skies in scattered fashion. The land in eastern Virginia and North Carolina is flat and flatter. The elevation at CPK is 20 feet, and that must be at the thickest part of the asphalt. At FFA, the tarmac registers a top of 13 feet. The only obstructions in between to watch out for are a couple of radio towers five minutes along our route, but they top out at a thousand feet and we were already at twice that altitude by the time we neared them.

The shoreline was quickly in sight, and we flew an

intersecting diagonal to the southeast. Shortly after we switched one of

the radios to the destination CTAF we heard a pilot claiming an approach

to two-zero. So much for the consistent nor-easter winds.

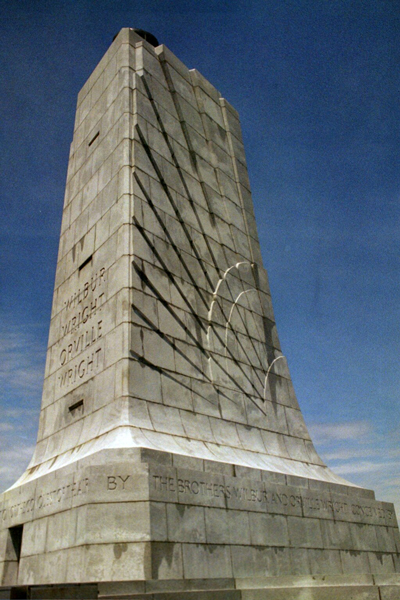

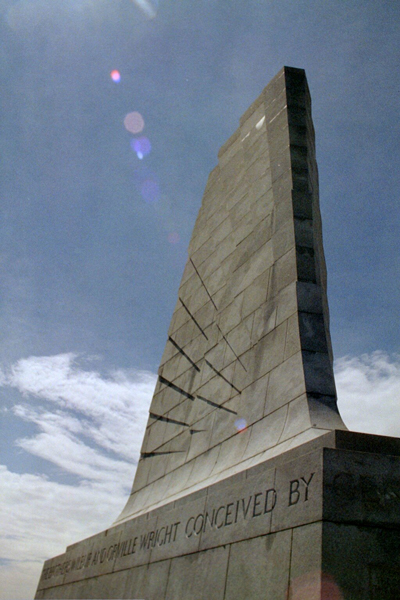

Before we saw the runway, we saw the monument, a 60-foot granite sculpture sitting on a star-shaped based at the top of a green hill gracefully carved with intersecting pathways. Stretching from the base of the hill toward our route of flight was a long meadow where the first powered flight paths were marked with stones.

Itís nice insurance to have an experienced flight instructor sitting next to you when the winds start blowing every which way, especially if you are a humble, 325-hour pilot. But it didnít get so dicey that I felt an urge to give up the controls. I didnít plan this trip to be flown in by someone else. I rode the plane down and executed one of the toughest landings in my short career. Not one of my smoothest, but certainly not one to cause embarrassment.

We first stopped in at the new AOPA pilot center, then scheduled to open in two days; the computers were hooked up and some last minute touches being made. Itís a small, unpretentious facility nestled among some trees just off the apron; it would no doubt see many thousands of visitors in the next seven months, and beyond.

We might have stopped in at the Memorial visitor center but it was closed pending completion of some renovations. Plus, I had a plane to catch, and many miles to go before I slept. We walked back to the airstrip, opened up the plane, called in vain for the flight attendant with our cocktails, and got ready to depart. human hair wigs

To my great delight the wind had shifted, and we were to take off on runway two, in the same direction as had been those historic flights. Also gracing our departure was the fact that the breeze was strong and steady...the very reason the Wright brothers had chosen this spot for their pioneering work. As we rose over the upside-down "20" at the end of the runway, Robert observed how quickly we had covered several times the distance Wilbur Wright had and in half the time. hair extensions uk

Returning on a reverse heading of 330 to CPK, I was feeling pleased to have accomplished this goal. It reflected my overall approach to being a pilot: you make a plan, fly the route and close it at the end, being flexible where needed. When we arrived at CPK, I taxied to the same spot in front of the terminal where Iíd found and pre-flighted the Skyhawk. It was a magenta patch of tarmac amidst a black field; like a winnerís circle.

I have a deep sense of honor to be an American and a pilot; to be following in my own small way the path made by the Wright brothers a hundred years ago. With deliberation and bright minds, they focused on the challenges of flight and pioneered new directions that changed civilization forever. Both their efforts and their success say a lot about our country, just as they hold us to higher standards for where we might go.

* * * * * * *

If you are interested in flying into FFA, here are some practical considerations. You can do as I did and fly into Norfolk, which is accessible by numerous commercial airlines, and rent a plane from Horizon Aviation. They are offering special packages; contact owner and pilot John Beaulieu at 757-421-9000 or 800-600-9990 or go on line to horizonflightcenter.com.

If you have the time and want to spend some of it on the Outer Banks, there are myriad places to stay. You are advised to wait until after the tourist season, if you have that flexibility; the crowds clear out in mid-September. If you like your food as fine as your flying weather, Owenís (252-441-7309) in Nagís Head on the beach road near Milepost 16 is a must; Lionel Shannon, one of the owners, is a pilot.

You can rent a plane at the Dare County Regional Airport in Manteo (MQI), which is only 3 minutes by air from FFA. They have Skyhawks, Pipers, and other aircraft, including a helicopter which you can rent. They are at 252-473-0318 and dillonsaviation.com/manteo/.

If you are flying yourself in and youíve read the airport directory information, you already know that you canít overnight at FFA. If you want to stay close, it would be in Manteo, though you should make your reservations for a parking spot well in advance. Many spaces are already taken and the price of pavement during high times isnít cheap.

An alternative is the Elizabeth City Regional Airport (ECG) where you might contact Flight Line Aviation at 252-338-5347 or 800-916-3226 or at flightlineair.com. They had a Cessna 150 and a Piper Cub at last check. Elizabeth City is 28 miles and 15 minutes from FFA by air, and a bit over an hour by car from the Outer Banks.

However you travel to Kill Devil Hills, make sure that you leave yourself several hours to enjoy the Wright Brothers Memorial. Itís not something you want to rush.

© 2003 - 2019 Tony Seton Communications